On October 6, 1927, the Jazz Singer debuted – and for the first time in history, film was given a voice. Less than two years later, in July of 1929, On With The Show added color. After these landmark films, cinema had irrevocably changed, and the adaptation of the new technologies was relatively swift. But on April 9, 1953, Man in the Dark became the first major 3D release, and the reaction was somewhat less impressive. If 3D is the way cinema ends, as many critics contest, Man in the Dark came with a whimper and not a bang: critics found no consensus, and until half a century later, our embrace of 3D films had been tentative at best.

Last August, Slate ran a piece entitled “Is 3-D Dead in the Water?” Two days ago, Roger Ebert declared that “3D doesn’t work and never will. Case Closed.” And since the Polar Express delivered us into an era of 3D revival in 2004, critics have been popularly proclaiming 3D as a dead medium walking. But what do the numbers show? Well, it appears the demise of 3D has been somewhat exaggerated.

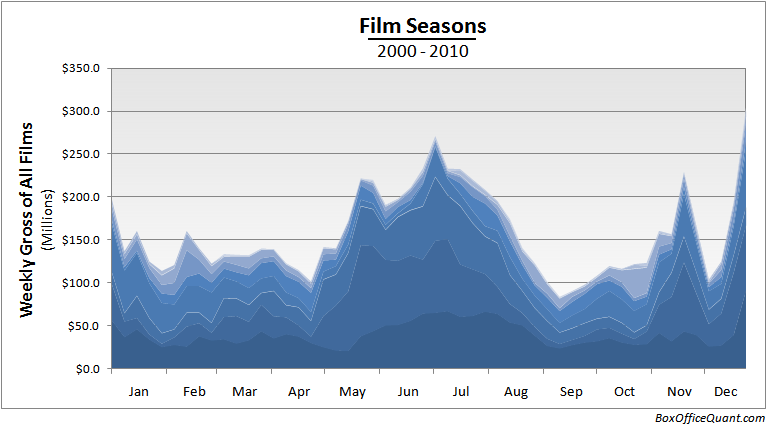

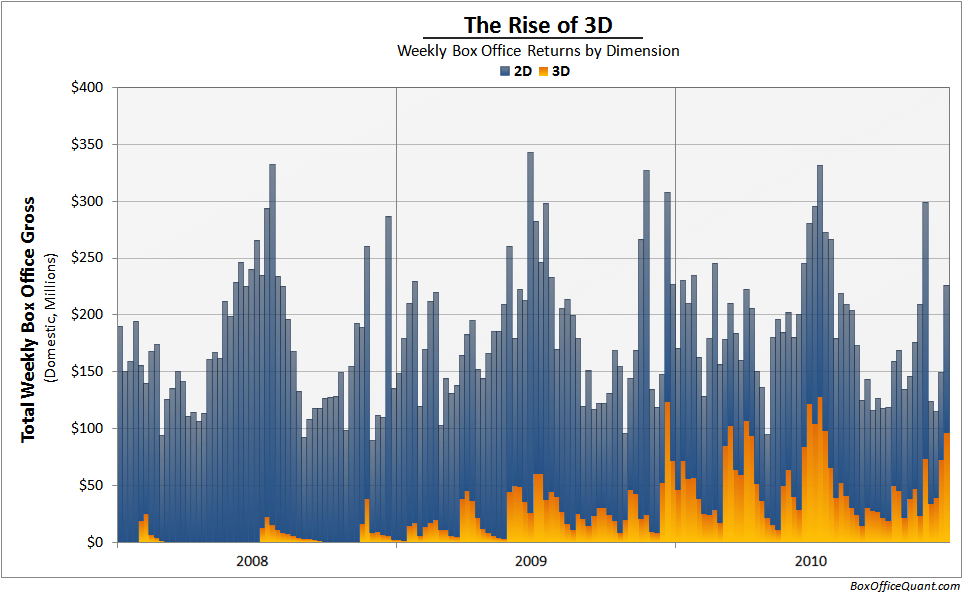

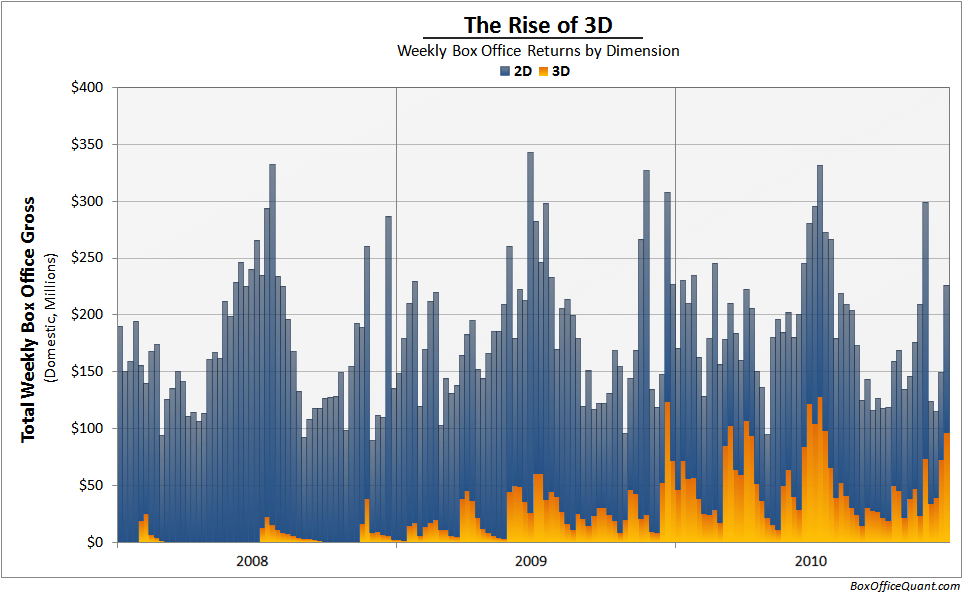

Let’s start with the recent state of 3D: Until 2008, the US revenue from films that were offered in 3D never accounted for more than 3% of all films. In 2009, they represented 16.3%, and in 2010, 31.4%. Keep in mind, those numbers include 2D versions of 3D films, such as the 2D screen revenue from Avatar. But even if that’s factored out, in 2010 the revenue from 3D-only was still 20.2%. To understand this trend visually, I’ve made two charts that show the rise in revenue from 3D-only screenings. Here’s a monthly breakdown from 2000-2010:

For a closer look, I’ve also created a weekly chart representing the last 3 years. It’s much easier to understand the granularity in this version, as you can track how individual 3D films are introduced, and how their revenue slowly decays:

From that perspective, 3D isn’t dead – in fact, it appears to be thriving. But this is only a snapshot of the moving industry, and only half the story.

To dive deeper, the previously mentioned Slate article did some insightful research on the per-theater revenue of 3D compared to 2D. Their results were that after 2004, 3D revenues per theater have been approaching 2D revenues, and that they’re now about equalized. Essentially, Slate has shown that 3D theaters previously were routinely filled with a larger audience, but that now audiences demand a 3D theater no more than 2D. This is a sign that the 3D market has matured, and the use of 3D theaters has been saturated. According to this analysis, any future rise in 3D as a share of all films can’t come simply from the novelty of 3D, but from a better use of 3D in films, or audiences becoming more accustomed to unwieldy polarizing glasses. And so, although the Slate article does make a convincing case for a deceleration of 3D film, I don’t believe it indicates that 3D film is likely to decline.

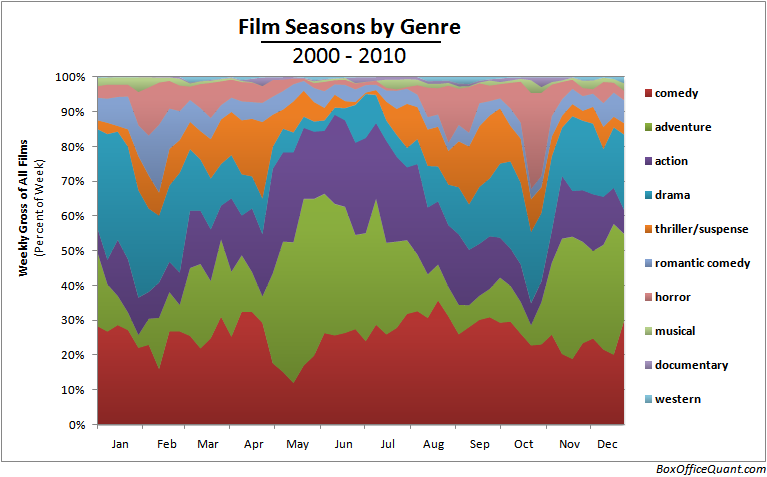

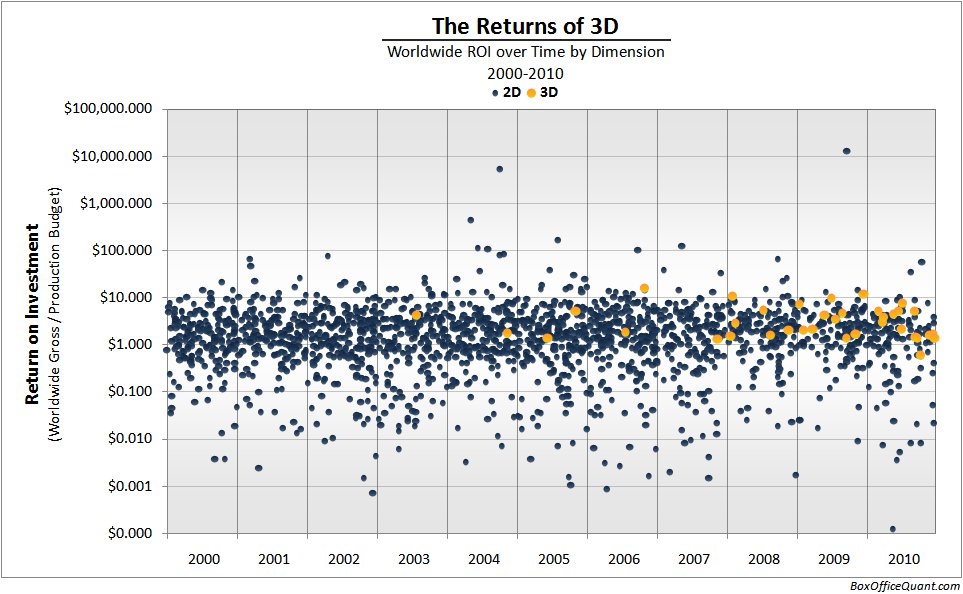

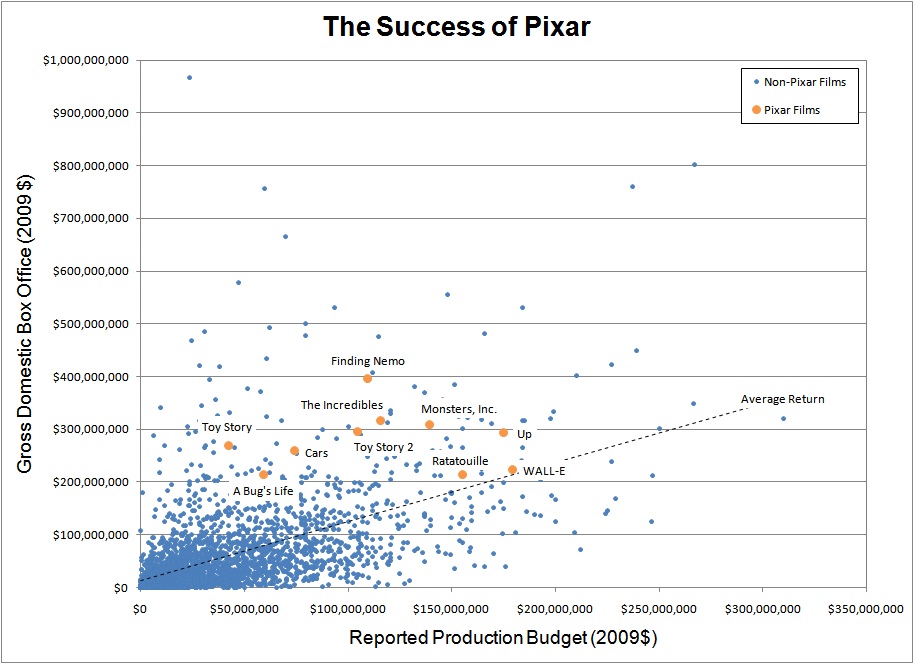

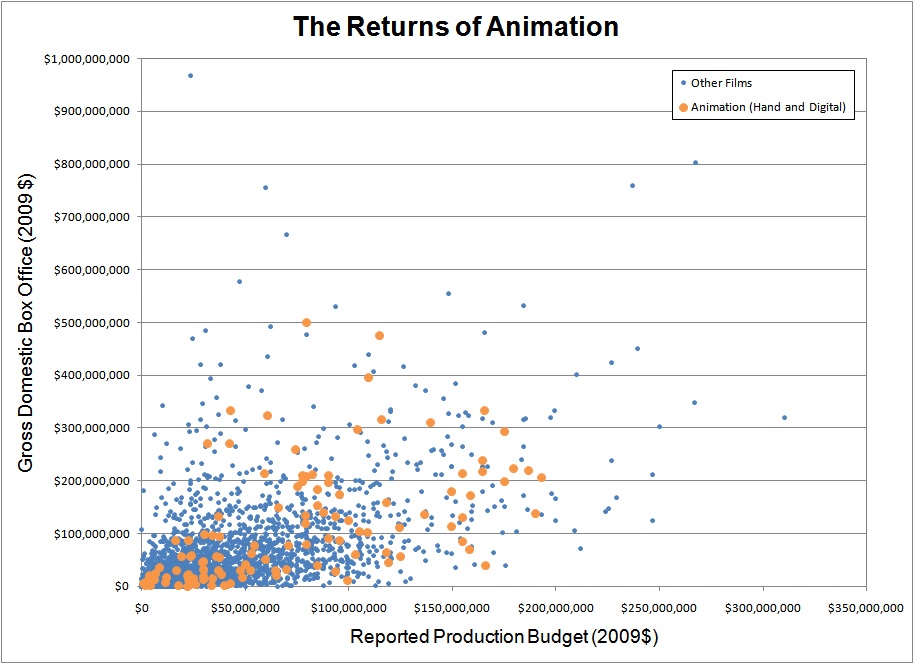

To further this analysis, I wanted to shed some light on the broader picture, and answer the larger question: how profitable are 3D films? Below are two charts: the first comparing the production costs to worldwide gross (in all films that have published production budget data from 2000-2010), the second showing returns to production budget over time.

First of all, the wayward dot in the top right is, of course, Avatar. Otherwise, as you can see, 3D films generally make much more money than 2D ($381M compared to $89.5M); but also cost much more ($105M compared to $35.6M). For each dollar spent on a 3D film, there’s an average return of $3.69; and for each dollar on a 2D film, there’s an average return of $2.51 in worldwide box office revenue.

However, given the high unpredictability of box office returns, this difference is statistically insignificant (there’s over a 20% likelihood that this differential return is the result of random chance). In addition, there is a bias in which films publicly report their production budgets, and this chart doesn’t speak to the fact that many films are selected for 3D treatment after having already been predicted for higher success. However, this information does strongly indicate that 3D films are not faring significantly worse than 2D, and any reasonable guess for the future, has to guess that 3D will be a growing factor in cinema.

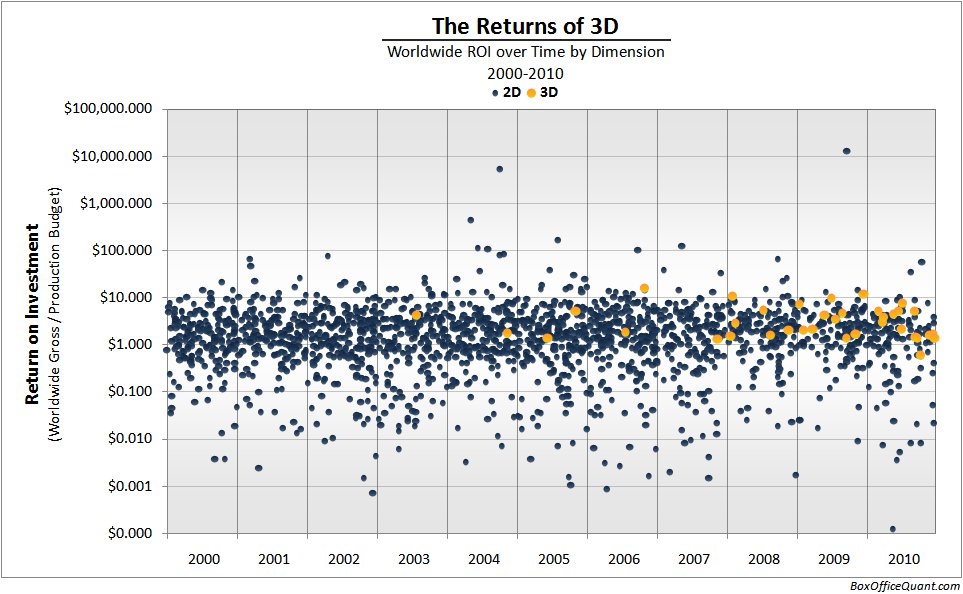

Lastly, I wanted to understand the development of 3D profits over time. In the chart below I’ve studied the return on production budgets – the amount earned worldwide divided by the amount spent in production. (Note the logarithmic scale, to fit in huge outliers such as Paranormal Activity and Super Size Me):

This final chart shows that 3D films are continuing to offer as much profit as ever; and their returns to production budget have actually remained remarkably constant (averaging less than a 0.1 cent change per year). In addition, you can see that all the 3D films have been much more predictable than 2D films. Where 2D films vary all over the map, 3D films (largely due to their big budgets) always give about the same return on investment, making them less risky, and even more desirable.

In the end, The Polar Express wasn’t the latest Jazz Singer. 3D isn’t the natural progression from 2D that only took time and technology to overcome. I believe it’s best considered a nearly different medium altogether, requiring a whole new set of tools to create well, and a new set of rules to evaluate and appreciate. In fact, I think the most apt comparison is that 3D, as it is now, is like the Silver Age of Disney: animation after The Lion King. We’ve seen the wonders of the new format (as well as some horrors), and the novelty is just now wearing off. But at the same time, even if each film is no longer quite as special, and there are as many misses as hits, the format is still in its newfound infancy – with a long way to mature.

Notes: The revenue from 3D was calculated by multiplying a film’s total revenue by that film’s share of revenue from 3D. However, the 3D share data are spotty – so when the data were unavailable, I assumed an average share for each film in 2010 so that the resulting weighted average of all films matched the reported 2010 average of 62.22%. In years previous to 2010, I assumed 62.22% where data were missing.

Statistical significance of 3D vs. 2D ROI based on a t-test of ROIs by dimension; the p-value is 0.22. ROI calculations were averages of ROI weighted by world gross, which is equivalent to dividing the sum of world gross by the sum of production budgets, for each dimension.

Revenues and production budgets from the-numbers.com. List of 3D films from boxofficemojo.com. Other sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7,8, 9, 10.